I took my first Risograph printing class at Nova Community Arts in LA this week and I fell completely in love with the process, the colours, the textures, the pink, the florescent pink…

You can now this print in my shop, with a 10% discount for SlowMotion Multitasking subscribers using the code SLOWMO2023!

Today I wanted to take you through some of the influences behind the illustration.

About 10% of the drawing was inspired by the poodles from the Bob Baker Marionette Theatre:

This 10%:

And the rest was inspired The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin:

Which is a glorious children’s book about exactly that:

Fun fact, I was in the Rachel Antonoff’s Fall 2014 Collection film, which was inspired by The Philharmonic Get Dressed!

Moonbow wrote a brilliant substack this week about the music of a good children’s book:

A good picture book can almost be whistled…All have their own melodies behind the storytelling. —Margaret Wise Brown

There have been so many gorgeous collaborations between children’s book illustrators and the theatre world, with Maurice Sendak creating some absolutely blinding operatic sets:

Houston Grand Opera production of “The Magic Flute.”

But there are also so many details within the world of the performing arts that feel akin to a good children’s book. Check out this romantic fact:

Watching a live theatre performance can synchronize your heartbeat with other people in the audience, regardless of if you know them or not.

I started reading musicians memoirs a few years ago, and I really loved A Romance on Three Legs by Katie Hafner about the life of the pianist Glenn Gould.

Gould was a renowned and controversial figure, and also rather famously anti applause, believing it could cause a performer to flub up, or not live up to expectations. As an act of resistance he launched (only half in jest) the:

“Gould Plan for the Abolition of Applause and the Demonstrations of All Kinds” or “GPAADAK”

Glenn’s piano tuner was Verne Edquist who was also a brilliant figure. Born blind, Verne had perfect pitch and synesthesia. Synesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon:

When you experience one of your senses through another. For example, you might hear the name "Alex" and see green. Or you might read the word "street" and taste citrus fruit. The word "synesthesia" has Greek roots. It translates to “perceive together.”

In Verne’s case, he saw the piano notes as colors. F was blue, C was a slightly lime green, D was a sandy hue, E was yellowy-pink, A was white, G orange and B dark green.

In the book, when Edquist remembers his childhood 60 years on, he does so through senses other than his sight:

"Each season had a distinctive aroma and its own set of sounds. In the winter ... the smell was of heavy wool socks drying near the stove. In spring it was the black soil warming and the sound of returning crows. Summer brought the smell of the poplars and the sounds of rustling leaves, frogs croaking in sloughs. ... In the summer came the grasshoppers."

This book also taught me that in the early 20th century, piano tuners outnumbered members of any other trade in English insane asylums. Blimey!

Yo-Yo Ma’s interview with Marc Maron is one of my favourites, especially this rather Goldilocks like origin story: As a kid, Yo-Yo Ma wanted to play the violin but he wasn’t very good. He then set his sights on the upright bass because he was the youngest child, so he wanted the biggest instrument to compensate. But the upright bass was too big for him, so at four years old he compromised and took up the cello. At 5 he had an existential crisis that he never chose the cello for himself, it was merely thrust upon him as a consolation prize for two instruments that didn’t fit him.

He also shares a tip that I think could be applied to any high stakes job: He loves breaking a string at the beginning of a performance because then no one expects anything from him. If you combined this ethos with with Glenn’s GPDAAK ordinance you could create the lowest stakes performance in history.

‘Gentlemen, More Dolce Please’ is Harry Ellis Dickson’s 1974 memoir of his time in the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In the opening chapters, Henry sets up the nuanced dynamics at play between each section:

There are some who don’t talk to one another. String players may profess to hate oboe players, and clarinetists may proclaim unifying hatred toward horn players, and cellists may go on despising each other forever, yet when the conductor gives the downbeat, there is a mysterious inner communication among all the players, feelings are submerged and through some minor miracles there is a concerted effort to make music. Afterwards they may all go back to hating each other! Yet, not too seriously, for the very nature of our profession tends to soften the human heart.*

*and make all their heart beats sync up.

Making sure anyone dropped in the centre of an orchestra pit can get out alive, Henry kindly provides a cheat sheet on each member of the orchestra’s particulars, from most troublesome to most lonely:

Cellists are the greatest source of trouble.

Viola players are the least troublesome, and most viola players smoke a pipe. Coincidence?

Oboe players are also trouble, and the unhappiest musicians, constantly bemoaning the fact that they have to play such a treacherous instrument.

The first oboist of every orchestra is usually not on speaking terms with the conductor.

Flute players are the best dressed, quietest and the easiest to get along with. Henry suspects this is because their instrument is the least amount of trouble to play.

Clarinetists are the cry babies of the orchestra.

Bassoonists are hobbyists - amateur astronomers or bow makers, and usually very smart. No one knows why. Henry suggests it should be studied.

French horn players live in the country and raises golden retrievers.

The harpist is the Beau Brummell of the orchestra. He plays so seldom that he has plenty of time to shop for new clothes, with the result that he is often taken, by strangers to be the conductor.

This description aligns perfectly with my best friend Tom Brown, who plays the harp:

And loneliest but not least:

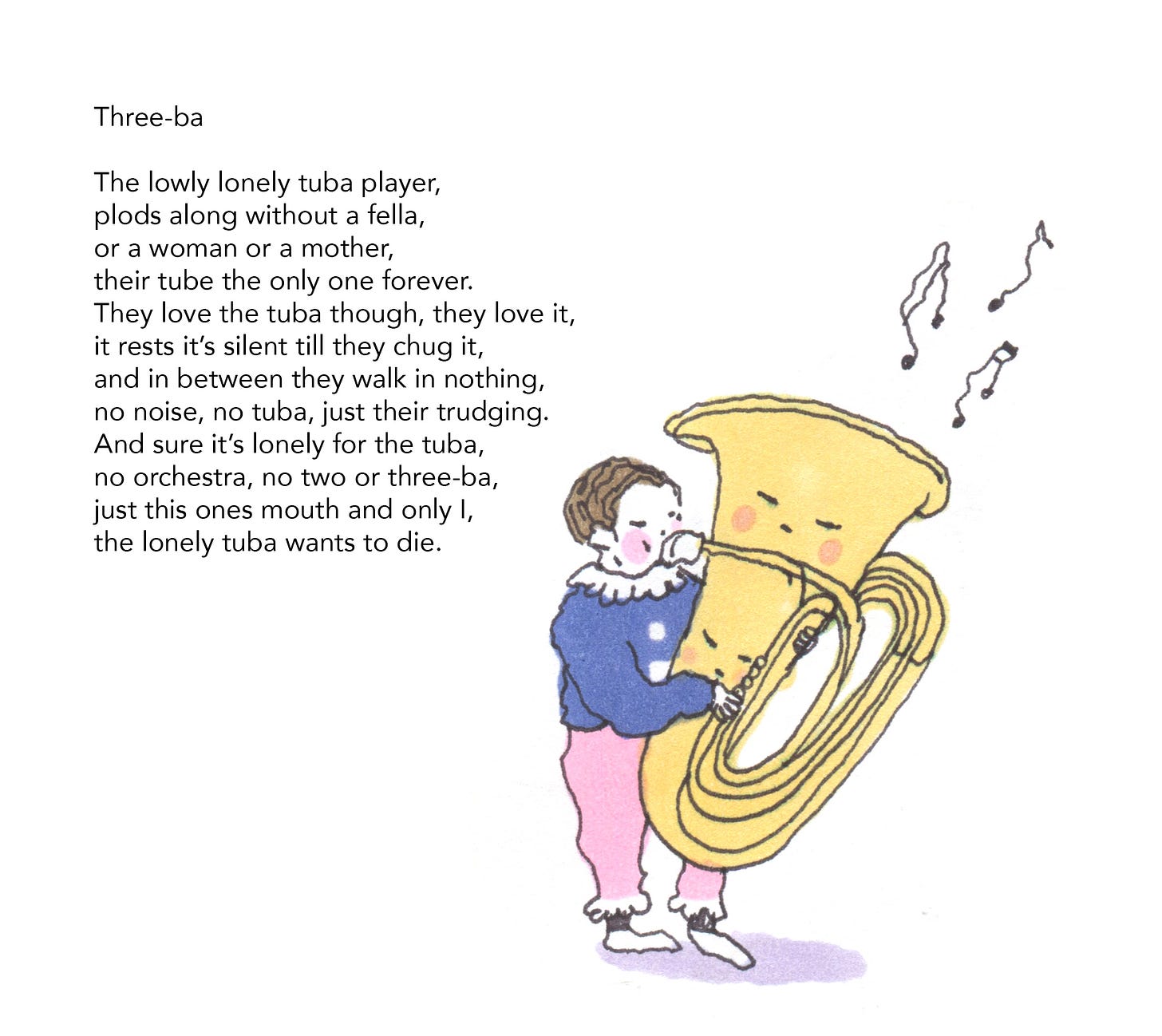

The Tuba player:

The lowly and lonely tuba player. There is only one in the entire orchestra and he enjoys a certain amount of prestige - and loneliness. Tuba players never talk. They are silent, morose, uncommunicative, but they sing to themselves. They have no common interests with any of their colleagues and, as a matter of fact, most tuba players feel that they don’t even belong in the orchestra. They usually strike up a strong friendship with the stage manager.

This paragraph gets top billing for me in the book and inspired this poem, which I have shared before but not next to it’s muse.

Next week i’ll be talking about some of my favourite children’s book illustrators and their contributions to the performing arts.

I adore these orchestral stereotypes so much 😭 and Nova Community Arts is fantastic!! They have such a sweet staff and fabulous array of workshops- I thought I recognized their riso machine on your story, so it's lovely to see that it is in fact where you printed these! :-)

This post brought me so much joy! The Philharmonic Gets Dressed was one of my absolute favorite picture books growing up!